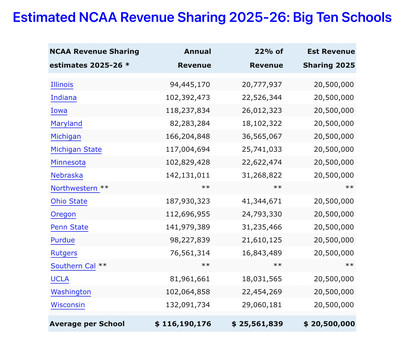

With every athletic department in the Big Ten generating varying amounts of revenue, yet expected to distribute the same $20.5 million to athletes in 2025, economic disparities are already starting to form:

For the likes of the Michigan Wolverines , the House vs. NCAA settlement was a small blip in the spending the athletic program already participates in every year, and it will be merely a percentage that must be allocated to athletes rather than other expenses.

But that’s not the case for the entire country, let alone the rest of the Big Ten. While Michigan and Ohio State bring in more than $160 million in athletic revenue every year, other Big Ten members such as Maryland, UCLA and Rutgers are much lower on the list, generating $81 million, $82 million and $72 million, respectively.

While these are still big numbers to the untrained eye, the Big Ten has been given direction to give $20.5 million to its athletes as part of direct revenue sharing during the 2025-26 academic year. While this is 10 percent of its revenue for Ohio State, it is 28 percent for Rutgers, according to NIL-NCAA. This could cause a massive disparity in salary caps, funds towards travel, training facilities expenses, staffing and many more costs that some programs just do not have the money for.

Under the direction of House vs. NCAA, Division I programs are asked to follow a model that gives 75 percent of the $20.5 million to football (coming out to $15,375,000), 10 percent to men’s basketball ($2,050,000), five percent to women’s basketball ($1,025,000) and five percent to the school’s other varsity sports.

While this is a nice, overarching framework, that may not be practical in the grand scheme of things. If a program like Rutgers wants to be competitive for years to come, other strategies may need to be enlisted regarding the allocation of that money.

How revenue sharing should be distributed across the Big Ten

The Wolverines have 29 varsity sports that Warde Manuel is dedicated to keeping. The Buckeyes have 36, Maryland has 20, Northwestern has 19. As you can see, giving five percent to sports other than football and basketball can vary greatly between schools, and this is where strategy may come into play.

Take UCLA for example, a powerhouse in women’s gymnastics. Or USC, the national leader in beach volleyball. If programs want to compete for both Big Ten championships and national championships, putting money into these smaller programs could be where we see dynasties start forming.

While football has the big, flashy number now, things can change very quickly when programs start getting ahead of the competition.

Say in a year that athletic departments have more flexibility with their allocation of revenue sharing money. With scholarship limits already increased for the upcoming academic year, there is little-to-no oversight on how schools should be spending their money. Sure, if Michigan is spending $146,000 per year on each of their football players , it may be more difficult to compete with that by taking money away from other football programs.

However, realizing there are other ways of competing may be the first domino that needs to fall for schools to pivot and find their lane elsewhere. Here is a list of one sport outside of football and basketball that each Big Ten should prioritize going forward based on recent success (i.e. Big Ten championships and standings):

- Iowa – Wrestling

- Illinois – Men’s and Women’s Golf

- Indiana – Men’s Soccer

- Maryland – Men’s and Women’s Lacrosse

- Michigan – Ice Hockey

- Michigan State – Ice Hockey

- Minnesota – Ice Hockey

- Nebraska – Women’s Volleyball

- Northwestern – Field Hockey

- Ohio State – Women’s Volleyball

- Oregon – Baseball

- Penn State – Ice Hockey

- Purdue – Wrestling

- Rutgers – Rowing

- USC – Beach Volleyball

- UCLA – Women’s Gymnastics

- Washington – Men’s and Women’s Track and Field

- Wisconsin – Women’s Volleyball

This list displays a very unique situation in which school’s of different sizes, athletic program revenue and geographical location could potentially run a particular sport if they allocate the right amount of money to that sport.

When asked questions about other potential revenue pools, Ohio State athletic director Ross Bjork said , “We thought volleyball could be a sport that could drive more revenue.”

Similarly, Penn State athletic director Dr. Patrick Kraft said , “We’re trying to be able to manage the money so that if we need to move on someone, no matter what the sport is, we have the ability to say, ‘Hey, there’s the No. 1 fencer in the world, and we need to go use rev-share to maybe tilt it our way, we’re going to be able to do that.”

From golf to wrestling to lacrosse and every sport in between, we could see Big Ten schools separate themselves from one another, taking home Big Ten championships, the prize money and the publicity that would come with it.

How can the Big Ten leave their mark as a conference, and individually?

Revenue sharing is meant to create many benefits for programs. It increases the scholarships a school can give out, giving programs more flexibility with recruiting and roster spots. It should make athletes happier about their worth, and it gives coaches and staff another resource to use when recruiting and retaining athletes. And, in theory, it evens out the competition, allowing for schools to have the same resources as one another to compete for championships.

However, there are still going to be economic and resource disparities. It is how each school handles these inequalities which will be the true test of sustainability and continuous success.